SATURDAY, JULY 15

The Panama Canal is what the US did best. It demanded the absolute support of a Government ruthless in pursuit of a benefit to the US. It demanded great vision and determination, brilliant planning and design, a massive workforce and vast finance. Miaflores dock is a short run from Panama city. Entrance is $8 for an adult, half price for pensioners. The museum is fascinating, clear explanations, geat models, insects, aquarium tanks. Indoors is air conditioned. My spectacles fogged each time I went outdoors and I slept thru most of the promotional film in the theatre.

And something bugged me.

A couple of hours passed before I came up with what. The canal is the only garbage-free zone in Central America. The grass is mown between the roadways and rails. The windows shine. None of the workers shout.

The restaurant is good. Prices range from reasonabale to luxury: $8 or #9 for hamburger or chicken with rice, $14 for Thai sea bass steamed in banana leaves, $35 for San Blas crab.

I stuck to bottled water and a pack of peanuts at the ground floor cafeteria.

Eat and watch the ships go by.

Most people watch from the fourth floor deck. Don't. Perspective takes size from the ships. Stay on the ground floor. The highest price transit ever passed thru today. The ship, MSC FABRIENNE, was built to the maximum size permitted thru the canal. She carries 4500 containers for a transit fee of $246,666. Looking up from gound level, the hard hats at the forward bulwarks looked to be a scattering of M&Ms. A lone pelican sat on the lock gates. Frigate birds floated overhead. Low cloud closed in from the Atlantic coast and rain hid the conical hills.

http//www.pancanal.com and watch the 24 hour live cam of ships passing thru the locks.

septuagenarian odyssies - US/Mexican border to Tierra del Fuego, Tierra del Fuego to New York, long ride round India

Saturday, July 15, 2006

JUST CAUSE

FRIDAY, JULY 14

We sat facing the Cathedral. The two white towers gleamed in the sun. The plump, motherly school teacher was reluctant to talk of people. She talked of the apartment buildings in the district that were destroyed in the invasion, that the buildings weren't luxurious but that they were an improvement and that there was a community feeling to the district.

She repeated the Bocas driver's accusation: that Noriega was easy to arrest. There were so many opportunities. He travelled out in the country, walked in the streets.

"So many people died."

She spoke of an entire family who were her neighbors. All were killed. The grandmother was seventy-three(my age). The youngest child was only six, a girl. The teacher said that none of the houses of the rich were damaged, none of the rich were killed, none of the captains.

Her friend nodded agreement. "They knew," she said. Her husband was second-in-command in Colon (cop?). At eight in the evening he sent one of his men with food and instructions that she wasn't to leave the house.

"It was against the poor," the motherly teacher insisted. Poor people weren't important. Artisans died and poor people who sold fried fish on the street corner and on the beach at weekend. "Very flavoursom," she assured me, "Fried with chili and with garlic."

Memory of the fish was a trigger. She wept, yet her tone of voice remained calm, almost wonderous, as she talked of her sister who had lived on the top floor of a building. "They shouted that everyone must come out into the street or they would be killed. There was so much blood in the elevator and bits of bodies, hands, legs, a head.

Her sister died two days after the invasion. "It was the shock..."

Her friend, the thin teacher, passed her a handkercief and she wiped her eyes.

"They lied," she said. "They killed more than five thousand people. They buried them with tractors. They are hidden there deep down in the area that is called Arenal. It was Henry Ford and Arias Calderon. They wanted to do it."

In the evening I talked with a successful businessman in his fifties, a computer expert. "Yes," he said, "There were thousands killed."

And, Yes, it would have been easy to capture Noriega. The invasion was uneccessary. He gave the booming Panamanian economy as the reason for the invasion. The canal would be handed over to Panama in ten years. The US was loosing control. The invasion was designed as a reminder for Panamanians as to their true status.

The US army named the invasion, Operation Just Cause.

I have not met a Panamanian who agrees.

We sat facing the Cathedral. The two white towers gleamed in the sun. The plump, motherly school teacher was reluctant to talk of people. She talked of the apartment buildings in the district that were destroyed in the invasion, that the buildings weren't luxurious but that they were an improvement and that there was a community feeling to the district.

She repeated the Bocas driver's accusation: that Noriega was easy to arrest. There were so many opportunities. He travelled out in the country, walked in the streets.

"So many people died."

She spoke of an entire family who were her neighbors. All were killed. The grandmother was seventy-three(my age). The youngest child was only six, a girl. The teacher said that none of the houses of the rich were damaged, none of the rich were killed, none of the captains.

Her friend nodded agreement. "They knew," she said. Her husband was second-in-command in Colon (cop?). At eight in the evening he sent one of his men with food and instructions that she wasn't to leave the house.

"It was against the poor," the motherly teacher insisted. Poor people weren't important. Artisans died and poor people who sold fried fish on the street corner and on the beach at weekend. "Very flavoursom," she assured me, "Fried with chili and with garlic."

Memory of the fish was a trigger. She wept, yet her tone of voice remained calm, almost wonderous, as she talked of her sister who had lived on the top floor of a building. "They shouted that everyone must come out into the street or they would be killed. There was so much blood in the elevator and bits of bodies, hands, legs, a head.

Her sister died two days after the invasion. "It was the shock..."

Her friend, the thin teacher, passed her a handkercief and she wiped her eyes.

"They lied," she said. "They killed more than five thousand people. They buried them with tractors. They are hidden there deep down in the area that is called Arenal. It was Henry Ford and Arias Calderon. They wanted to do it."

In the evening I talked with a successful businessman in his fifties, a computer expert. "Yes," he said, "There were thousands killed."

And, Yes, it would have been easy to capture Noriega. The invasion was uneccessary. He gave the booming Panamanian economy as the reason for the invasion. The canal would be handed over to Panama in ten years. The US was loosing control. The invasion was designed as a reminder for Panamanians as to their true status.

The US army named the invasion, Operation Just Cause.

I have not met a Panamanian who agrees.

TWO TEACHERS

FRIDAY, JULY 14

I returned to Casco Viejo district late this morning. Yesterday I discovered a comida that sells fresh, unsweetened pear juice. Today I drank two glasses ($0.50). Later I sat with two women on a bench in the Cathedral Square. The women were school teachers. They asked if I enjoyed their country and what I enjoyed. I spoke truthfully of the openess I encountered in the people and of the beauty of the country. Pleased, they asked if I had visited the church with the Golden Altar (the altar is a survivor of Henry Morgan's fire. I had and I had walked widely and said that the Casco Viejo would be very beautiful again once it was all restored.

"It will be for tourists," the younger of my companions said. "That is what the Government plans. It will be too costly for ordinary people, for the poor."

This teacher was in her fifties, a thin somewhat severe woman, black, her hair dragged back in a tight tuft.

Mention of the poor started the elder teacher talking of the US invasion of Panama in 1989. She is a plump motherly woman, 64 years old, her hair dyed a golden brown and set in quite youthful curls. She held a transparent plastic file case on her lap. Her fingers were chubby and she wore a gold wedding band together with an engagement ring set with a fragment of green stone.

I returned to Casco Viejo district late this morning. Yesterday I discovered a comida that sells fresh, unsweetened pear juice. Today I drank two glasses ($0.50). Later I sat with two women on a bench in the Cathedral Square. The women were school teachers. They asked if I enjoyed their country and what I enjoyed. I spoke truthfully of the openess I encountered in the people and of the beauty of the country. Pleased, they asked if I had visited the church with the Golden Altar (the altar is a survivor of Henry Morgan's fire. I had and I had walked widely and said that the Casco Viejo would be very beautiful again once it was all restored.

"It will be for tourists," the younger of my companions said. "That is what the Government plans. It will be too costly for ordinary people, for the poor."

This teacher was in her fifties, a thin somewhat severe woman, black, her hair dragged back in a tight tuft.

Mention of the poor started the elder teacher talking of the US invasion of Panama in 1989. She is a plump motherly woman, 64 years old, her hair dyed a golden brown and set in quite youthful curls. She held a transparent plastic file case on her lap. Her fingers were chubby and she wore a gold wedding band together with an engagement ring set with a fragment of green stone.

CASCO VIEJO

THURSDAY, JULY 13

Casco Viejo is a slum undergoing gentrification under Government guidance. Streets have been paved. Official buildings gleam. Buildings awaiting resurection have been given a coat of pastel paint. Other buildings have rows of bells beside new doors. The doors are lined with steel. Police patrol - some on pushbikes and wearing shorts and biker helmets. The first upmarket restaurants have opened behind closed doors (to protect the electrically cooled air). The poor sit on doorsteps. I enter a store in search of ballpoint. The goods on sale are in one half of the room: a few Panama hats, black waistcoats embroidered with golden animals. A grey-haired lady has collapsed on a sofa beside a cutting table in the remaining part of the store. Her husband sits at a work table trimming silk lining for a pair of evening slippers. The lady is overweight and has difficulty in rising. I appologise for disturbing her.

"It is the heat," she says, and wipes her forehead on her forarm...The heat and she has a headache.

I have been walking an hour. My feet ache and I agree as to the heat.

She pours me a glass of water from a plastic jug.

I would be rude in not drinking - possibly unwise in drinking. Travel is full of such quanderies. I sit in a wicker chair beside the work table and write up these notes.

Casco Viejo is a slum undergoing gentrification under Government guidance. Streets have been paved. Official buildings gleam. Buildings awaiting resurection have been given a coat of pastel paint. Other buildings have rows of bells beside new doors. The doors are lined with steel. Police patrol - some on pushbikes and wearing shorts and biker helmets. The first upmarket restaurants have opened behind closed doors (to protect the electrically cooled air). The poor sit on doorsteps. I enter a store in search of ballpoint. The goods on sale are in one half of the room: a few Panama hats, black waistcoats embroidered with golden animals. A grey-haired lady has collapsed on a sofa beside a cutting table in the remaining part of the store. Her husband sits at a work table trimming silk lining for a pair of evening slippers. The lady is overweight and has difficulty in rising. I appologise for disturbing her.

"It is the heat," she says, and wipes her forehead on her forarm...The heat and she has a headache.

I have been walking an hour. My feet ache and I agree as to the heat.

She pours me a glass of water from a plastic jug.

I would be rude in not drinking - possibly unwise in drinking. Travel is full of such quanderies. I sit in a wicker chair beside the work table and write up these notes.

POINTS OF VIEW

THURSDAY, JULY 13

The old part of Panama City dates back to the 1670s. Tourists would expect it to be called Old Panama. It is called the Old Compound, Casco Viejo. Panama Viejo is a collection of overgrown ruins. The buildings were beautiful before they were put to the torch by that great English privateer, Henry Morgan. They were beautiful before they were put to the torch by that vicious murderous English pirate, Henry Morgan.

By family, I am both British and Hispanic. My great grandfather, Ramon Cabrera, was a Spanish terrorist. He built his terrorist band into an army, won battles and became the Marques del Ter, Conde de Morella. I must make a speach in Morella on the 6th of December in celebration of his 200th anniversary. Doing so, I will glorify a terrorist and become a criminal according to the inane laws proposed by the present British Government and passed by Parliament. The Government is sadly short of historians. Most are lawyers. Historians would have known better than commit British troops to Iraq and Afghanistan.

The old part of Panama City dates back to the 1670s. Tourists would expect it to be called Old Panama. It is called the Old Compound, Casco Viejo. Panama Viejo is a collection of overgrown ruins. The buildings were beautiful before they were put to the torch by that great English privateer, Henry Morgan. They were beautiful before they were put to the torch by that vicious murderous English pirate, Henry Morgan.

By family, I am both British and Hispanic. My great grandfather, Ramon Cabrera, was a Spanish terrorist. He built his terrorist band into an army, won battles and became the Marques del Ter, Conde de Morella. I must make a speach in Morella on the 6th of December in celebration of his 200th anniversary. Doing so, I will glorify a terrorist and become a criminal according to the inane laws proposed by the present British Government and passed by Parliament. The Government is sadly short of historians. Most are lawyers. Historians would have known better than commit British troops to Iraq and Afghanistan.

Friday, July 14, 2006

TO PANAMA CITY

WEDNESDAY, JULY 12

I slept last night in David at the Hotel Iris on the Cathedral square, a good clean room with a/c and hot water in the evening, not in the morning ($14). Today I rode to Panama City on the PanAmerican Highway, 450 Ks. I encountered heavy rain part of the way. Guide books report Panama City as dangerous - even by daylight. My destination is the Hotel Caribe on Central Avenue, a big American style highrise easy to find and with a garage for the Honda. I bargain the room rate down $2 to 25. The bed is great. The TV controller doesn't work. Nor does the light in the bathroom. I am too tired to complain and I am mad in the morning at finding the Honda moved and punctured.

Hey, the old fool is going to have to pay to have it fixed - licking of lips.

No.

I push the bike up the ramp and round two blocks to a puncture repair shop. We remove wheel and tyre in time for an electricity cut. Result, I waste the morning - if wasting is being directed to a street stall that serves a great breakfast with two cups of coffee for $.80 and finding a perfect hotel with a hot water power shower, a/c, cable and a good restaurant for $16.

First impressions of Panama City? Cabs stop so you can cross the road. And I haven't been mugged.

I slept last night in David at the Hotel Iris on the Cathedral square, a good clean room with a/c and hot water in the evening, not in the morning ($14). Today I rode to Panama City on the PanAmerican Highway, 450 Ks. I encountered heavy rain part of the way. Guide books report Panama City as dangerous - even by daylight. My destination is the Hotel Caribe on Central Avenue, a big American style highrise easy to find and with a garage for the Honda. I bargain the room rate down $2 to 25. The bed is great. The TV controller doesn't work. Nor does the light in the bathroom. I am too tired to complain and I am mad in the morning at finding the Honda moved and punctured.

Hey, the old fool is going to have to pay to have it fixed - licking of lips.

No.

I push the bike up the ramp and round two blocks to a puncture repair shop. We remove wheel and tyre in time for an electricity cut. Result, I waste the morning - if wasting is being directed to a street stall that serves a great breakfast with two cups of coffee for $.80 and finding a perfect hotel with a hot water power shower, a/c, cable and a good restaurant for $16.

First impressions of Panama City? Cabs stop so you can cross the road. And I haven't been mugged.

STRAWBERRIES AND CREAM

TUESDAY, JULY 11

The Atlantic coast is hot and damp and jungly. Cross the divide and you are in a drier country, a country worked by people. Dairy farms with Swiss names cling to the mountains high on the divide. Lower you are in a rolling grassland of wealthy ranchers. Race horses graze neatly fenced paddocks. Turn up hill and you reach the vegetable and fruit farms of Bloquet and Volcan. Bloquet is sick with an infestation of weekend housing developments. Why must the houses be so utterly charmless? However my goal is reached on the left at the entrance to the town: FRESAS MARIE. Here, close to the equator, I sit in the sun and eat fresh picked strawberries with whipped cream - surely a luxury equal to eating a fresh peach in the Antartic.

Late afternoon and I ride to David, a modern city, and find a comfortable hotel on the central square. Exploring the city, I discover a Domino Pizza Parlor. The delivery bikes are Honda 125 Cargos. I order a pizza and have a delivery rider photograph my own Cargo amongst its pizza twins.

WOW, WHAT A DAY

TUESDAY, JULY 11

The road from Almirante to David first follows the mountainous coast. At each corner there is a fresh and seemingly more beautiful view down across jungle to a sea strewn with wooded islands.

I take photographs and question whether one is a better view than another.

I recall why I have traveled without a camera for years.

The camera is a barrier. I am thinking camera, looking for views and judging views rather than simply absorbing and enjoying an incredible ride.

Yesterday, from the ferry, I counted four lines of mountains rise one above the other. The fourth is the divide. I reach the summit. Nothing separates me from Africa other than the curvature of the earth. Look ahead and only the curvature of the earth separates me from New Zealand, Australia, the Far East. I have been warned of the wind that rips across the ridge. No one mentioned the fear, the sense of being less than a pinhead.

The road from Almirante to David first follows the mountainous coast. At each corner there is a fresh and seemingly more beautiful view down across jungle to a sea strewn with wooded islands.

I take photographs and question whether one is a better view than another.

I recall why I have traveled without a camera for years.

The camera is a barrier. I am thinking camera, looking for views and judging views rather than simply absorbing and enjoying an incredible ride.

Yesterday, from the ferry, I counted four lines of mountains rise one above the other. The fourth is the divide. I reach the summit. Nothing separates me from Africa other than the curvature of the earth. Look ahead and only the curvature of the earth separates me from New Zealand, Australia, the Far East. I have been warned of the wind that rips across the ridge. No one mentioned the fear, the sense of being less than a pinhead.

BREAKFAST IN ALMIRANTE

TUESDAY, JULY 11

Joni runs the best breakfast place in town. She is part Irish going back three generations and the rest West Indian. Her grandad came to Almirante from Jamaica to work for United Fruit. Joni recalls Almirante under United Fruit. The town was clean and ordered. Everything worked. The trains ran on time. The same is said by the Old Folk of Mussolini's Italy and Nazi Germany and the Indian subcontinent under British rule.

An old man enters with packets of dough.

"Just the one today, Pappi," says Joni.

"As you wish, my love," comes the answer.

Then we are back to comparing United Fruit with Chiquita Banana. "Chiquita is all measurements," says Joni. "All they care is measurements. They measure everything."

Later I talk for half an hour with a successful local businessman. He is Jewish. What is happening in the Middle East appauls him. Here, in Panama, Jewish, Syrian and Lebanese do business together; most are IN business together.

"United Fruit was good and bad," he says. Staff were housed according to rank. Houses were maintained by the Company. United Fruit moved employees from Company town to Company town, saw to their health, their pensions, educated their children, decided what stock was available in the Company store. In return, employees were loyal to the Company rather than to themselves and their roots were in the company rather than in Almirante. Now they feel lost and abandoned.

"The Company was king, paternalistic. Chiquita is accountants."

The businessman has a fear of a powerful investor moving in, a financial entity witth no care for the environment. He asks me to tell my readers to support Green Peace.

READERS, SUPPORT GREEN PEACE...

Joni runs the best breakfast place in town. She is part Irish going back three generations and the rest West Indian. Her grandad came to Almirante from Jamaica to work for United Fruit. Joni recalls Almirante under United Fruit. The town was clean and ordered. Everything worked. The trains ran on time. The same is said by the Old Folk of Mussolini's Italy and Nazi Germany and the Indian subcontinent under British rule.

An old man enters with packets of dough.

"Just the one today, Pappi," says Joni.

"As you wish, my love," comes the answer.

Then we are back to comparing United Fruit with Chiquita Banana. "Chiquita is all measurements," says Joni. "All they care is measurements. They measure everything."

Later I talk for half an hour with a successful local businessman. He is Jewish. What is happening in the Middle East appauls him. Here, in Panama, Jewish, Syrian and Lebanese do business together; most are IN business together.

"United Fruit was good and bad," he says. Staff were housed according to rank. Houses were maintained by the Company. United Fruit moved employees from Company town to Company town, saw to their health, their pensions, educated their children, decided what stock was available in the Company store. In return, employees were loyal to the Company rather than to themselves and their roots were in the company rather than in Almirante. Now they feel lost and abandoned.

"The Company was king, paternalistic. Chiquita is accountants."

The businessman has a fear of a powerful investor moving in, a financial entity witth no care for the environment. He asks me to tell my readers to support Green Peace.

READERS, SUPPORT GREEN PEACE...

HUNGER

MONDAY, JULY 11

The ferry is slow. We load trucks and cars in Bocas and head back to Almirante. A young mulatta woman asks if I have a novia. I answer that my wife is my novia. She tells me that many Gringos on Bocas have novias. I believe her. She has failed in seeking a Gringo - partly, perhaps, because she gnaws her nails. She is also awkward in her movements, consumptively thin and devorced of charm. She has no money and hasn't eaten. Fish and fluffy pancakes cost $1.50. She doesn't thank me. One of the drivers and I chat with the cook who earns $250 a month. She is a competent cook of simple food. Most billionaires have more sophisticated tastes.

The ferry is slow. We load trucks and cars in Bocas and head back to Almirante. A young mulatta woman asks if I have a novia. I answer that my wife is my novia. She tells me that many Gringos on Bocas have novias. I believe her. She has failed in seeking a Gringo - partly, perhaps, because she gnaws her nails. She is also awkward in her movements, consumptively thin and devorced of charm. She has no money and hasn't eaten. Fish and fluffy pancakes cost $1.50. She doesn't thank me. One of the drivers and I chat with the cook who earns $250 a month. She is a competent cook of simple food. Most billionaires have more sophisticated tastes.

MILLION DOLLAR HOMES

MONDAY, JULY 10

The ferry from Almirante is on its second run. It unloads a couple of 4X4s and a freezer truck at Bocas. The Mack trucks are on board. I park the Honda and sit with the drivers outside the ferry's cafe. A driver points to the first of the million dollar homes in the Bocas archipelago. The house sits on a point. A second house is a further kilometer down the same island and we spot a third before the ferry turns in to the private dock on Frefor island. Frefor is an island without a village. It is an island without Panamanians. The developer and his staff are American. They speak English. Most of the workers are of West Indian background. They are big men dressed in American work clothes. They are delivered in shifts by launch. They appear well fed and carry themselves with a certain arrogance. It is an arrogance often evident in those employed by the very rich.

The sun breaks thru the clouds and the sea gleams between patches of mangrove. Frefor is a long jungle cloaked ridge. The million dollar homes are on the far side facing the open sea. The ferry turns in to the private dock. I watch the Mack trucks dump their gravel a hundred yards uphill. Hopefully a sufficiency of billionaires will enable the drivers to buy their own trucks.

WATER TAXIS

village and plush hotel

MONDAY, JULY 10

Bocas cabs are outboard-powered boats. A tourist party arrives by launch from Almirante. They pile up-market luggage on the dock. They require a boat to take them fifty meters to a plush new hotel on the water front - a confectionery of white paint that has cost (I am told and believe) a million dollars. An indigenous local poles his boat over to the dock. The hotel's white greeter spots half an inch of water in the bilges. He instructs the tourists to wait while he fetches a better boat. He ignores the boatman. The boatman sponges the offending water out of the bilges. He is a patient man, perhaps a little closed. I ride with him over to a village on the next island. A rash of wooden docks stick out from the shore. The boatman patrols a while, collecting passengers one by one. He drops a health worker off at a bar on the return trip to Bocas. A young Israeli woman (resident here for three years)works at the plush hotel. The boatman drops her at the hotel's dock. The boatman and I laugh together. The trip has been fun.

EDUCATION IS A PRIVLEDGE

MONDAY, JULY 10

Light rain falls as I ride the length of Bocas. The road rises thru low hills. The crest is capped with a patch of bamboo forest. Weighted by rain, the bamboos arch over the road. Much of the land is cattle ranch. Lots are advertised for sale. A development of cheap tasteless wooden holiday homes would benefit from a can of gasoline and a match. The bay the far end of the island faces the open sea. Turn left and a sand track leads to the Institue for Tropical Ecology and Conservation. The teachers are North American. So are the students. Some are from Canada, most from the US. I read the literature (ITEC is a not-for-pofit organisation based in Gainesville, Florida).

http//www.itec-edu.org

The school is on a sand beach protected by a reef. A further reef projects from the next island. Students eat at a next door restaurant. The restaurant has a small orchard: breadfruit, guanavara, a calabas tree. I order coffee and watch, between the palm trees, waves break on the reefs. A lone pelican sits on a marker post 50 meters out. Two parots nibble my ankles beneath the table.

The parents of a student I talk with have paid $2,500 for his five week course. He is from New England, a great kid, quarter Indian (as in Asia). He intends entering business once he has his Masters. Business is exciting. He believes that the Iraq war is the right war. He is having a great day. So am I. I resist relating the opinions voiced by the driver of the Mack truck.

I stop off at the Smithsonian Institute on the way back into town. Staff are out on the reef. The adminsitrative secretary gives me a beautifully produced catalogue of the Institute's work in Panama. I will send the catalogue to my son, Mark, a marine biologist.

Light rain falls as I ride the length of Bocas. The road rises thru low hills. The crest is capped with a patch of bamboo forest. Weighted by rain, the bamboos arch over the road. Much of the land is cattle ranch. Lots are advertised for sale. A development of cheap tasteless wooden holiday homes would benefit from a can of gasoline and a match. The bay the far end of the island faces the open sea. Turn left and a sand track leads to the Institue for Tropical Ecology and Conservation. The teachers are North American. So are the students. Some are from Canada, most from the US. I read the literature (ITEC is a not-for-pofit organisation based in Gainesville, Florida).

http//www.itec-edu.org

The school is on a sand beach protected by a reef. A further reef projects from the next island. Students eat at a next door restaurant. The restaurant has a small orchard: breadfruit, guanavara, a calabas tree. I order coffee and watch, between the palm trees, waves break on the reefs. A lone pelican sits on a marker post 50 meters out. Two parots nibble my ankles beneath the table.

The parents of a student I talk with have paid $2,500 for his five week course. He is from New England, a great kid, quarter Indian (as in Asia). He intends entering business once he has his Masters. Business is exciting. He believes that the Iraq war is the right war. He is having a great day. So am I. I resist relating the opinions voiced by the driver of the Mack truck.

I stop off at the Smithsonian Institute on the way back into town. Staff are out on the reef. The adminsitrative secretary gives me a beautifully produced catalogue of the Institute's work in Panama. I will send the catalogue to my son, Mark, a marine biologist.

BOCAS HOSPITAL

MONDAY, JULY 10

Bocas hospital has an emergency unit with aircon. An indigious child with an infected foot is the only other patient. A nurse sits me on a chair and sets to work with tweezers and blade. The removal is painless. The nurse dreams of being a writer. She doesn't read. Read two pages and she has a headache. The headaches began sooon after she left University. She has medical training: sugesting an eye test seems presumptious. She despatches me round the block to pay. I see, thru an open window, a skeletal old man curled up on a bed. He groans as he attempts to roll over. I hunt down the cashier's window and pay $5.

Bocas hospital has an emergency unit with aircon. An indigious child with an infected foot is the only other patient. A nurse sits me on a chair and sets to work with tweezers and blade. The removal is painless. The nurse dreams of being a writer. She doesn't read. Read two pages and she has a headache. The headaches began sooon after she left University. She has medical training: sugesting an eye test seems presumptious. She despatches me round the block to pay. I see, thru an open window, a skeletal old man curled up on a bed. He groans as he attempts to roll over. I hunt down the cashier's window and pay $5.

BOCAS

MONDAY, JULY 10

Bocas is beautiful. A small island, it is on the World map. It has arrived. It is a non-tourist tourist destination. The architecture is wood-shuttering Cape Cod-Carribean. Every building on Main Street sells something: food, booze, tours, real eastate.

Two weeks on the island and tourists enjoy the delusion of belonging. They become prey for male mid-age ex-trendies with tans and pony tails. Hustlers and marks sit in conference in bars and restaurants. On sale is the dream of owning some easy business, life without stress, a yearly holiday of 365 days, sun, sand and sex.

The scene is familiar: Ibiza, Block Island, Hydra, Mykinos...

I need a hospital. Eight days have passed since I sliced my hand. The stitches are due out.

Bocas is beautiful. A small island, it is on the World map. It has arrived. It is a non-tourist tourist destination. The architecture is wood-shuttering Cape Cod-Carribean. Every building on Main Street sells something: food, booze, tours, real eastate.

Two weeks on the island and tourists enjoy the delusion of belonging. They become prey for male mid-age ex-trendies with tans and pony tails. Hustlers and marks sit in conference in bars and restaurants. On sale is the dream of owning some easy business, life without stress, a yearly holiday of 365 days, sun, sand and sex.

The scene is familiar: Ibiza, Block Island, Hydra, Mykinos...

I need a hospital. Eight days have passed since I sliced my hand. The stitches are due out.

Thursday, July 13, 2006

DIFFERENT WORLDS

MONDAY, JULY 10

Fast passenger launches leave for Bocas from Almirante when they have a full load, say every half hour. The crossing takes twenty minutes; the fare is $3 and subsidised by Government. I take the slow car ferry due to leave at 6 a.m. I arrive early on the Honda, buy my ticket ($10 each way).

A car loads first, then the man directing the loading calls, "Simon, bring your bike." I have been traveling three months. Hearing my name called in a strange land at 5.30 a.m. is oddly warming. So is chatting with a couple of truck drivers. Six Mack trucks are carrying sand and gravel to one of the islands where a Gringo (the drivers´term) is constructing a housing development for billionaires. One of the billionaires is a famous basketball player. The drivers recount that the player´s house will cost two million dollars (they learnt this on TV).

Inland a thin mist clings to the trees along the mountainside. Red lights flash on the Cable & Wireless radio masts. The flood lights along Chiquita's pontoon are exactly spaced. Thick black cloud lies over the sea to our left. The water is almost black. An inbound passenger launch leaves a white trail. The smell of frying chicken drifts from the open window behind us and a tin spoon clatters against a cooking pot.

I eat a breakfast of round fluffy pancakes with sausage. Meanwhile the conversation has turned to bikes. A driver has a broken Yamaha. A second driver claims to be a specialist. "Buy the parts," he says: "We'll put it together on a Sunday. Start at six." He acts assembling the engine. " Ping pam, ping pam, ping pam, finshed by four."

This same specialist was in the army. He talks about the US invasion of Panama. "Twenty-three dead," he says of US soldiers. "It's a big lie, Pappi. We shot them in the sky. Pom," he goes, aiming an imaginery rifle. "Pom, pam. I tell you, Pappi, twenty-three is a big lie. And how many they kill, thousands."

All these dead for one man: the US could have grabbed Noriega any time, claims the driver. The invasion was on the 20th. On the 18th, Noriega was visiting a US base. (I have no idea if this is true) Now Iraq is the same. The driver believes that the invasion was a practice run. He says that the Americans believe they can do anything they want. The other two drivers nod their agreement. Perhaps they agree from fellowship for a fellow driver.

I am becoming obsessive in my demand for detail (or recognise my obsession). I am interested in the cost of a used Mack truck. The one driver's Mack is twenty-years old, value $5000. This driver used to drive mules (the motive part of a trailer truck) till Chiquita pushed down the price. $450 is the frieght on a load of gravel out to the island. The crossing takes two-and-a-half hours. The driver makes two trips most days, six days a week. He leaves home at 4:30 in the morning and gets back at 11 p.m. He is paid by the trip. A normal month, he earns $500.

Fast passenger launches leave for Bocas from Almirante when they have a full load, say every half hour. The crossing takes twenty minutes; the fare is $3 and subsidised by Government. I take the slow car ferry due to leave at 6 a.m. I arrive early on the Honda, buy my ticket ($10 each way).

A car loads first, then the man directing the loading calls, "Simon, bring your bike." I have been traveling three months. Hearing my name called in a strange land at 5.30 a.m. is oddly warming. So is chatting with a couple of truck drivers. Six Mack trucks are carrying sand and gravel to one of the islands where a Gringo (the drivers´term) is constructing a housing development for billionaires. One of the billionaires is a famous basketball player. The drivers recount that the player´s house will cost two million dollars (they learnt this on TV).

Inland a thin mist clings to the trees along the mountainside. Red lights flash on the Cable & Wireless radio masts. The flood lights along Chiquita's pontoon are exactly spaced. Thick black cloud lies over the sea to our left. The water is almost black. An inbound passenger launch leaves a white trail. The smell of frying chicken drifts from the open window behind us and a tin spoon clatters against a cooking pot.

I eat a breakfast of round fluffy pancakes with sausage. Meanwhile the conversation has turned to bikes. A driver has a broken Yamaha. A second driver claims to be a specialist. "Buy the parts," he says: "We'll put it together on a Sunday. Start at six." He acts assembling the engine. " Ping pam, ping pam, ping pam, finshed by four."

This same specialist was in the army. He talks about the US invasion of Panama. "Twenty-three dead," he says of US soldiers. "It's a big lie, Pappi. We shot them in the sky. Pom," he goes, aiming an imaginery rifle. "Pom, pam. I tell you, Pappi, twenty-three is a big lie. And how many they kill, thousands."

All these dead for one man: the US could have grabbed Noriega any time, claims the driver. The invasion was on the 20th. On the 18th, Noriega was visiting a US base. (I have no idea if this is true) Now Iraq is the same. The driver believes that the invasion was a practice run. He says that the Americans believe they can do anything they want. The other two drivers nod their agreement. Perhaps they agree from fellowship for a fellow driver.

I am becoming obsessive in my demand for detail (or recognise my obsession). I am interested in the cost of a used Mack truck. The one driver's Mack is twenty-years old, value $5000. This driver used to drive mules (the motive part of a trailer truck) till Chiquita pushed down the price. $450 is the frieght on a load of gravel out to the island. The crossing takes two-and-a-half hours. The driver makes two trips most days, six days a week. He leaves home at 4:30 in the morning and gets back at 11 p.m. He is paid by the trip. A normal month, he earns $500.

BANANA BOAT

SUNDAY, JULY 9

Almirante was a United Fruit town. Now the name is Chiquita Banana. Entry to Chiquita's air conditioned office building is thru a guarded security gate in the port area. Two of Chiquita's fleet lie alongside a concrete wharf. The wharf belongs to Chiquita. I require clearance from the Big Men in the open-plan first-floor office. The Big Men are well fed. They are Panamanians with a West Indian heritage and speak English. A lot of telephoning to and fro takes place before I am issued with a visitor's badge and a green hard hat. The Polish Chief engineer wears the baggy shorts and grey T-shirt he wore last night in the Chinese restaurant. I wonder if he slept in them. The ship is sailing in an hour and he conducts me on a whirlwind tour of the engine department. The control room is screens and switches. A steel door leads to the bank of computers that control both ship and cargo. The Chief demonstrates opening and closing one of the many valves that ballance the fuel load. Next we visit the engine which seems small for such a big task. Later on the tour and down a deck level, I realise how deep are the cylinders. We visit pump rooms and more pump rooms, filter rooms and more filter rooms, heating units for the fuel oil, cooling units for the cargo, climate control for the cargo, generators, spare generators, more generators. The tour is designed to impress. I am impressed.

We return to the control room.

"Harrison Ford, bullshit," announces the Chief. He acts the actor spining imaginary control wheels. "Open this valve, open that valve. Big Captain in white uniform save everyone. All bullshit." The Chief jabs a finger at a flashing red light. "Captain, idiot. You think he know what is? Idiot. All idiots. Bulb break, he call me how to fix."

What else did I learn? That bananas are put to sleep while traveling. They reach their destination, are given a whiff of gas, wake up and turn yellow. I know what gas and the climate control that puts them to sleep. And I know that Chiquita has sold off the trucks and trailers that transport the containers from the plantations to the wharf. The new owners are in debt to the bank. They can't argue prices.

Almirante was a United Fruit town. Now the name is Chiquita Banana. Entry to Chiquita's air conditioned office building is thru a guarded security gate in the port area. Two of Chiquita's fleet lie alongside a concrete wharf. The wharf belongs to Chiquita. I require clearance from the Big Men in the open-plan first-floor office. The Big Men are well fed. They are Panamanians with a West Indian heritage and speak English. A lot of telephoning to and fro takes place before I am issued with a visitor's badge and a green hard hat. The Polish Chief engineer wears the baggy shorts and grey T-shirt he wore last night in the Chinese restaurant. I wonder if he slept in them. The ship is sailing in an hour and he conducts me on a whirlwind tour of the engine department. The control room is screens and switches. A steel door leads to the bank of computers that control both ship and cargo. The Chief demonstrates opening and closing one of the many valves that ballance the fuel load. Next we visit the engine which seems small for such a big task. Later on the tour and down a deck level, I realise how deep are the cylinders. We visit pump rooms and more pump rooms, filter rooms and more filter rooms, heating units for the fuel oil, cooling units for the cargo, climate control for the cargo, generators, spare generators, more generators. The tour is designed to impress. I am impressed.

We return to the control room.

"Harrison Ford, bullshit," announces the Chief. He acts the actor spining imaginary control wheels. "Open this valve, open that valve. Big Captain in white uniform save everyone. All bullshit." The Chief jabs a finger at a flashing red light. "Captain, idiot. You think he know what is? Idiot. All idiots. Bulb break, he call me how to fix."

What else did I learn? That bananas are put to sleep while traveling. They reach their destination, are given a whiff of gas, wake up and turn yellow. I know what gas and the climate control that puts them to sleep. And I know that Chiquita has sold off the trucks and trailers that transport the containers from the plantations to the wharf. The new owners are in debt to the bank. They can't argue prices.

MOST BEAUTIFUL TRUCK STOP IN THE WORLD

perfect truck stop

SUNDAY, JULY 9

I bought new batteries for my camera yesterday. They were flat when I reached that awful bridge. I am out of bed by 5.30 this morning and biking back with fresh batteries loaded. I pass three trucks parked on the roadside below a small thatched cafe. I take my photographs (two are on the blog) and stop at the cafe for breakfast. The cafe is on a ridge 80 meters up a dirt track from the road. It is not much of a place. The floor is cement as is a kitchen counter. Wooden posts support the thatch roof. A couple of hammocks hang from hooks. The upright chairs are old and have carved leather backs. Sit at one of the four tables and you look down over rich jungle to the island-spotted gulf of Bocos del Toro.

A girl, 8, sweeps the floor. Her brother, four years older, is lighting the fire outside in a half-drum. The mother fetches me a cup of freshly made coffee.

I question the daughter on her school and whether she enjoys books. Being a pompous old man, I tell her that education is the only road to freedom.

The mother agrees. "There is so much competition now," she tells me.

A white butterfly in a hurry flies directly across my view. Perhaps it is aware that life is short. Most butterflies appear aimless. Here they are copper-colored and red and yellow. Birds work up a racket while I eat (the standard pancakes and chopped steak in sauce). The sun is out. We are up a thousand feet and the air is cool. The family house is a further fifty meters or so up the ridge and has its back to a wood. This must be the most perfect truck stop in the world. Riding back to Almirante, I realize what an idiot I am in talking freedom to the young girl. What do I know? Maybe she is already close to Paradise.

CHINESE DINNER

SATURDAY, JULY 8

I had a weird night. Dinner at a Chinese restaurant. A drunk Polish Chief engineer off a banana boat sat with me. He shouted a good deal. Much of his shouting concerned deck officers being idiots. A second subject was racism. Foreigners (non-Polish) believed Polish people were all racists and idiots. "Not so," the Chief insisted.

As proof that he was not a racist, he presented his recent promotion of a Fillipino to Chief Engineer´s rank.

I had chosen a corner table, my back to the wall. The Fillipino crew were seated across the restaurant watching a boxing fight on TV between a Fillipino and an American.

"They love me," insisted the Chief Enginneer. "I am their King. Of course they love me."

He bellowed for the newly promoted Engineer to come pay hommage - which he did, a quiet man, well mannered, wearing round spectacles. The Chief paraded him as he woulod have a prize dog, then dismissed him and returned to his criticism of deck officers. "I show you ship. Tomorrow I show you ship. You see. All f...ing idiots."

We made a date for 10 a.m.

I had a weird night. Dinner at a Chinese restaurant. A drunk Polish Chief engineer off a banana boat sat with me. He shouted a good deal. Much of his shouting concerned deck officers being idiots. A second subject was racism. Foreigners (non-Polish) believed Polish people were all racists and idiots. "Not so," the Chief insisted.

As proof that he was not a racist, he presented his recent promotion of a Fillipino to Chief Engineer´s rank.

I had chosen a corner table, my back to the wall. The Fillipino crew were seated across the restaurant watching a boxing fight on TV between a Fillipino and an American.

"They love me," insisted the Chief Enginneer. "I am their King. Of course they love me."

He bellowed for the newly promoted Engineer to come pay hommage - which he did, a quiet man, well mannered, wearing round spectacles. The Chief paraded him as he woulod have a prize dog, then dismissed him and returned to his criticism of deck officers. "I show you ship. Tomorrow I show you ship. You see. All f...ing idiots."

We made a date for 10 a.m.

Tuesday, July 11, 2006

ALMIRANTE

station hotel

SATURDAY, JULY 8

Almirante has seen better days. We drove down Main street in the truck passed the Station Hotel. A guest sneezes and the hotel will crumble.

The driver had a delivery to make to the Fereteria Casa Rosa. Thank God, a new hotel had opened across the street, rooms on the upper floor. I may have been the first guest. The room was big, the bed was comfortable, the bathroom functioned, the a/c was silent perfection. Add a fan to keep any mosquitos at bay. One minus, the TV wasn't cable! It will be next week. A friendly mother and daughter run the Hotel Puerto del Almirante. On the next block a lady of Jamaican/Irish decent runs the best breakfast place I've eaten at: $1.75 for chopped steak in pepper sauce served with round, flat, fluffy pancakes and coffee. Add a room rate of $12.50, no wonder I made Almirante my base for three nights.

THANKS TO THESE TWO MEN

Monday, July 10, 2006

A BRIDGE TOO FAR

truly scary

1. other people

had problems

2. a long way

SATURDAY, JULY 8

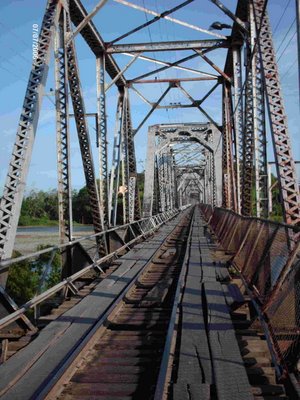

I have been warned. The Bridge of the Americas is all and more than I expected. It is nearly three hundred meters long. The planks are uneven and slippery. Many are missing. A bigger bike than the Honda could fall thru the gap between planks and lower guard rails. Much of the wire safety netting fastened between upper and lower guard rails is missing. I travel the first twenty yards before the bike slips. Desperate to save the Honda, I tip inwards across the rails. I lie pinned under the bike. I look down between the sleepers at the river in spate from the recent rains. Truck drivers run down the track and heave the Honda off my leg. They join in warning me that the bridge is dangerous - as if I require warning. They lift me onto my feet and the bike into the back of a truck. I sit up front. The driver spends the entire fifteen kilometers to Almirante warning me of further perils. He is carrying building supplies to the wharehouse of the biggest store in town. The store owner recommends a hotel across the road run by mother and daughter. The rooms are on the first floor: $25 for a room with bath, TV, and a/c. I protest to the daughter that I am a pensioner. She immediately halves the rate. Bush telegraph is fully functional in Almirante. I sit at a table in the back of a nearby Chinese restaurant and receive the commiserations of half the populace.

COSTA RICA CARIBBEAN

SATURDAY, JULY 8

At first the road to Panama follows the coast. Even the shanty towns of Costa Rica`s capital looked cared for. Here, on the Caribbean coast, wooden house rot unpainted amongst the palm trees: evidence of poverty or of neglect? The road swings inland. Puffs of smoky cloud spill from pockets in the mountains bordering the banana platations. A river divides Costa Rica from Panama. Waiting in line at Costa Rican Immigration takes a few minutes. I am alone at Customs. Panama is the far end of a Chiquita Banana railway bridge. Loose and uneven planks lie end to end across the sleepers each side of the rails. Rain has been spitting and the planks are as slippery as a greased pole. I edge across in first gear, one foot on the rail, one on the planks. Two truck drivers are at the Customs window in Panama. I tell them of my fear. They warn me of a second bridge on the road to Almirante; the second bridge is in worse condition and three times as long. Cars have crashed. For bikes it is very dangerous. Many people have fallen. Recently an American broke his arm. A German broke a leg.

At first the road to Panama follows the coast. Even the shanty towns of Costa Rica`s capital looked cared for. Here, on the Caribbean coast, wooden house rot unpainted amongst the palm trees: evidence of poverty or of neglect? The road swings inland. Puffs of smoky cloud spill from pockets in the mountains bordering the banana platations. A river divides Costa Rica from Panama. Waiting in line at Costa Rican Immigration takes a few minutes. I am alone at Customs. Panama is the far end of a Chiquita Banana railway bridge. Loose and uneven planks lie end to end across the sleepers each side of the rails. Rain has been spitting and the planks are as slippery as a greased pole. I edge across in first gear, one foot on the rail, one on the planks. Two truck drivers are at the Customs window in Panama. I tell them of my fear. They warn me of a second bridge on the road to Almirante; the second bridge is in worse condition and three times as long. Cars have crashed. For bikes it is very dangerous. Many people have fallen. Recently an American broke his arm. A German broke a leg.

LIMON

FRIDAY, JULY 7

Nine hours on the internet. Central America is bananas. Yesterday I visited a 4,000 hectar banana plantation. Today I trespass on the grave of the United Fruit Company. Limon was once a Company town. A photograph (circa 1902) of United Fruit`s headwooden headquarters building shares wall space with two photographs of banana boats alongside United Fruit`s wharf. In Morales, Guartemala, another United Fruit town, locals were made to step off the sidewalk when encountering Company officials. Limon's waterfront is a sad relic of those days of regal glory. I stroll at night alonf the sidewalk below the sea wall. Loving couples share the wall with family groups, a clump of elderly men, five kids kicking a ball. At a table in the town's smartest hotel, five elderly men are recording a local radio program. I sit at the bar, drink a beer, chat with the manageress. A designer enters to show the manageress the mundane logo for this year´s October carnival (young gnome). I dine at a Chinese restaurant on Wonton soup. I have the best room of my travels on the second floor at the Hotel Miami for $17: a/c, hot hot water, cable TV. The internet cafe round the corner had a/c; connecting the Toughbook was easy and uploaded pictures onto the blog.

Nine hours on the internet. Central America is bananas. Yesterday I visited a 4,000 hectar banana plantation. Today I trespass on the grave of the United Fruit Company. Limon was once a Company town. A photograph (circa 1902) of United Fruit`s headwooden headquarters building shares wall space with two photographs of banana boats alongside United Fruit`s wharf. In Morales, Guartemala, another United Fruit town, locals were made to step off the sidewalk when encountering Company officials. Limon's waterfront is a sad relic of those days of regal glory. I stroll at night alonf the sidewalk below the sea wall. Loving couples share the wall with family groups, a clump of elderly men, five kids kicking a ball. At a table in the town's smartest hotel, five elderly men are recording a local radio program. I sit at the bar, drink a beer, chat with the manageress. A designer enters to show the manageress the mundane logo for this year´s October carnival (young gnome). I dine at a Chinese restaurant on Wonton soup. I have the best room of my travels on the second floor at the Hotel Miami for $17: a/c, hot hot water, cable TV. The internet cafe round the corner had a/c; connecting the Toughbook was easy and uploaded pictures onto the blog.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)